I think I have always been fascinated by imagination. When I was a teenager, it seemed to be the element that separated the true artists, musicians, poets, and writers from the rest of us. It was a quality that transcended mere talent and hard work. It was mysterious.

When I listened to the singer/songwriters of my time, like James Taylor, Paul Simon, Jackson Browne, and Joni Mitchell, they all seemed to have imagination in abundance. So did the Beatles, Sting, Peter Gabriel, and Bruce Springsteen. All of them produced music and lyrics that looked afresh at the universals of love, loss, tragedy, beauty, and the spirit.

I studied them, pulled apart their lyrics and musical structure, looking for keys to their brilliance. What they did seemed effortless, an economy of words and composition that didn’t waste a note or a syllable.

I noticed the same in some of my favorite writers, beginning with Hemingway, a master at creating a scene with as few words as possible. In different ways than Hemingway, but no less imaginative, were Saul Bellow, Kurt Vonnegut, John Gardner, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Joan Didion, and James Lee Burke.

All of them, writers and musicians, drew on an inner power that expressed a more spacious vision than I found within myself. I wondered if you had to have lived a respectable number of years to write in that way. But many of these icons were doing some of their best work in their twenties and thirties. Maybe you had to travel the world on a merchant freighter, be a short-order cook, do time in a county jail, start a business and fail at it, get married and divorced, or give up a law practice to write full time. Well, no, not really. All of that might give you experience to draw from, but it wasn’t necessary. There was something else.

Anne and Barry Ulanov’s book, The Healing Imagination, emphasizes imagination as the creative activity of the psyche and the soul. We work with the images that appear to us, often unbidden. “They just happen,” they write, “They arrive in consciousness from the unconscious, like a wisp of spirit. . . they speak of another life running in us like an underground river-current.”

I’ve come to believe that this creative impulse in all of us originates with the Holy Spirit, even if we don’t recognize it as such. No matter how it plays out and through whom it appears, imagination is critical to our humanity and to our spiritual growth.

The development of imagination, for example, in the act of creative writing, whether it be fiction, essays, drama, sermons, songs, or poetry, is an exercise in dropping the barriers to one’s inner life. “Art’s desire,” comments Jane Hirshfield, in Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World, “is not to convey the already established but to transform the life that takes place within its presence.” The presence of an unexpected newness.

We see this newness in the parables and sayings of Jesus. They are a wellspring of wisdom, never depleted on multiple readings. I believe Jesus discovered how to listen to his unconscious, that depth which is in all of us, and how to open his mind and spirit completely to God. What he offered the disciples was a glimpse of that imaginative power.

Our reflex is to reject these images. The new breaks in upon us often without form, almost unrecognizable at times. Hirshfield comments in Ten Windows that it’s a question of how much of the random, chaotic, and the mysterious we are willing to admit into our lives, assuming we have a choice.

We can also draw a distinction between hope and imagination. We can think of hope as an extension of present reality, but with the possibility of God breaking in to make something new. Then imagination is the seed from which hope grows. Our difficulty is in perceiving and believing that God can bring a new creation from the chaos of our situation.

Cease to dwell on days gone by

and to brood over past history.

Here and now I will do a new thing;

this moment it will break from the bud.

Can you not perceive it (Isa. 43:18,19)?”

The Ulanov’s note that our play as children in imaginatively creating personalities for our stuffed animals and toys, sustains our capacity as adults to enjoy and create images of God from tradition, Scripture, and experience. “Imagination digs the soil,” they write, “and brings the water so that what comes to us grows . . . In this space between our single unconscious life and our shared conscious life with others, imagination plays and heals.”

For poets, artists, and the rest of us, what really matters in life begins with questions: Who are we now? What shall we be? Where will we find healing for our souls? How can we respond to hatred and indifference with love, justice, and mercy?

Since the first thing to go in a crisis is imagination, our subversion of the status quo is plain: we must begin to imagine together the newness of what our worship, our service to our communities, and our spiritual arts could look like in the face of such global shifts as climate change, the displacement of millions, and the presence of COVID in our midst.

Barry Casey taught religion, philosophy, ethics, and communications for 37 years at universities in Maryland and Washington, DC. He is now retired and writing in Burtonsville, Maryland. More of the author’s writing can be found on his blog, Dante’s Woods. Email him at darmokjilad@gmail.com. His first book, Wandering, Not Lost: Essays on Faith, Doubt, and Mystery, is now available.

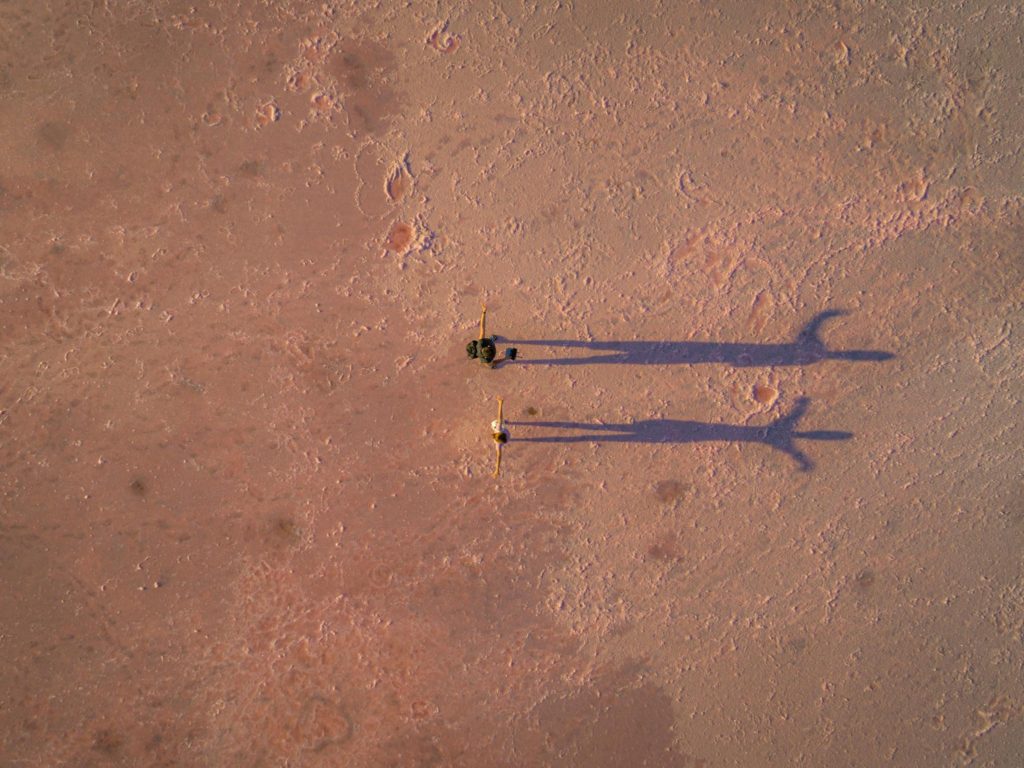

(Photo by Ken Cheung on Unsplash)